| Contents > “Roar Britannia?” by Bridget Deane |

| Page 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Despite the accusations of incompetence thrown at both the military and civil administration in Malaya, there still remained the hope that Singapore would be held and defended to the last. A cartoon by Strube illustrates this (Fig. 9), showing a lion poised to repel advancing panthers (Japan). Note the squadron of dragonflies in support of the panthers. By the beginning of February, when this cartoon was published, it seemed inevitable that Singapore would fall – the causeway between the island and mainland had been blown up in a bid to slow down the Japanese advance. How long ‘Fortress Singapore’ could hold out was a matter of speculation, but the roaring, aggressive, lion pictured here would surely suggest to readers of the newspaper that the Imperial forces (British, Australian and Indian troops) would be giving their all in defending Singapore.

Figure 9. Daily Express, February 3, 1942 Sidney Strube

However, on 15 February, 1942 General Percival surrendered to Japanese forces with allied losses (killed and captured) of 138, 708 (Connaughton, 1994, p. 32). Why and how had the impregnable fortress of Singapore been lost so easily? The Australians blamed the British; the British blamed the Australians; the British blamed the British … in fact it would probably be fair to say that the rest of the world, including the Axis powers, pointed the finger at Britain. As Murfett (2002) comments,

Scapegoats are invariably needed when disasters occur. And, alas, the British do fit the bill – not least because many people (and not just those from the Australasian Dominions) depended upon them for their defence and survival and in the end – not matter which way you cut it – the British let them down. This is not empty populist rhetoric – it sadly happens to be an indisputable fact of life’ (pp. 20-21).

The bulldog was in the doghouse, the lion was no longer king of the jungle. Cartoonists now turned their attention to Australia and the continuation of the battle against Japan.

The cartoons below, one Australian and one British, show Australia’s determination to keep fighting, yet the way in which the country is portrayed there is a notable difference in the approach of the cartoonists.

(from left to right) Figure 10. Daily Express, February 19, 1942 Sidney Strube / Figure 11. The Argus, March 17, 1942 Mick Armstrong

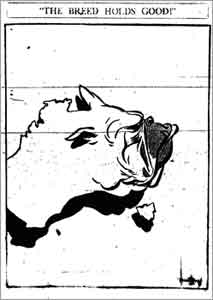

In Figure 10, Strube has created a lion’s head out of western Australia – a rather handsome fellow. On a tin hat, set at a rakish angle, are the words ‘total mobilisation’, and its whiskers are bayonets; this lion is ready and waiting. Note also the sporting analogy in the title of the cartoon – ‘THE HOME PITCH’ – Australia now found itself on the front line. A lion has been used to characterise Australia, linking the country back to Britain. Would this lion be a formidable enemy for the Japanese? For me, the bulldog, drawn by Mick Armstrong, looks like a much more fierce some opponent (Figure 11). This time, the east side of Australia has been used to create the animal’s face, and the country looks angled, so the bulldog – an ugly specimen – is looking up towards Japan, a tooth showing and bottom lip protruding. The title of the cartoon ‘THE BREED HOLDS GOOD!’ suggests that Australians are showing the same determination and spirit as the British population, stoically defending their island against Nazi Germany. It is interesting that the Australian cartoonist, Armstrong, has chosen a bulldog to represent his country, whereas Strube has used the lion. Was it the aggressive nature of the bulldog that appealed, rather than the British (imperial) lion which had lost its roar and prestige with the fall of Singapore?

Editorial cartoons relating to the invasion of Malaya and subsequent fall of Singapore bring colour to written accounts of this episode during the Second World War. It is through contemporary newspaper reports as well as the cartoons that we can gain an understanding of what the general public in both Australia and Britain knew of events taking place in the Far East. What is emphasised in the cartoons used for this paper is that at the time, it was the civil administration that was blamed for the disastrous defence of Malaya. However, it should be taken in to account that the Press had a hand in apportioning the blame. Next in line was the Britain itself, represented by the sleeping lion, which needed to be roused from its snoozing to take responsibility for the security of its territories and dominions in the Far East. As Murfett (2002) points out it was the British who were responsible for the loss of Singapore. It is also clear from these editorial cartoons that the ties between Australia and Britain were strong, despite the fall of Singapore and the feeling that British had let everyone down badly. The use of the lion or bulldog to characterise each country expresses the close familial relationship between them.

Finally, these cartoons were primarily to entertain, but they also gave praise or criticised. They were not part of the official propaganda campaign in either country yet they would have encouraged morale and influence opinion, but they did not intentionally mislead or misinform the public; rather the editorial cartoon reflects what was known about the situation in the Far East at that time and illustrate this for their audience. Darracott (1989) comments that 'Cartoons can have a part in widening the range of our understanding of the past …' (p.150). Moreover, for a researcher the drawings and captions illuminate the written record, provoke thoughts and questions and raise a smile, just as was originally intended by the cartoonists who created them.

Figure 12. Daily Mirror (London) March 26, 1942,

Philip Zec

| Page 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Contents > “Roar Britannia?” by Bridget Deane |