| Contents > “Roar Britannia?” by Bridget Deane |

| Page 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

Also, a number of journalists were critical of British people living in Malaya, including Ian Morrison (1943) but most notably Cecil Brown, an American reporter. One of his articles “The City of Blimps, apathetic and unprepared” was reproduced by the Daily Express (14 January, 1942), in defiance of a ban by military authorities on the publication or broadcast of any of his work. This piece seems to be the origin for the whisky-swilling sahib stereotype, and provoked a response from L.D. Gammas, MP and former Malayan civil servant:

-

All this talk about whisky swilling by rubber planters, tin miners and blimpish civil servants is a disgraceful thing. … If Malaya is unable to hold off the invaders today it is not their fault but the fault of the Home country’s one-sided disarmament policy for 20 years after the last war. Now is the time to send men, guns, tanks and warplanes to Malaya and to stop wrongly criticising our fellow-countrymen there.

(Quoted in the Straits Times, British Community in Malaya Championed, 20 January, 1942)

Elphick (1995) makes an interesting point about newspaper reports concerning the behaviour of European residents of Singapore, suggesting that these stories were started by ‘certain British newspaper correspondents out to make a good copy, …’ (p. 276). No doubt the readers of these newspapers would have been influenced by these reports as well as the visual images provided by editorial cartoons in their assessment of the British in Malaya. But how accurate was this assessment?

The Civil Defence of Malaya, collated by Sir George Maxwell (1946), gives a detailed description of the roles played by British men and women in the battle to stop the Japanese advance down the Malayan peninsula; the majority of men were involved in civil defence or the volunteer forces (army, navy and airforce), while many women contributed as nursing auxiliaries, manning first aid posts and blood transfusion units, and working in canteens and social clubs for soldiers as well as fund raising activities. While it cannot be ignored that there were some who contributed little to the war effort, overall the majority did. Therefore, it was not without cause that Sir George Maxwell admonished the British public for the way in which

-

in complete ignorance of the facts, it abused indiscriminately the civil servants, the planters, the European women, the Malays, and the entire civilian community for what was, from beginning to end, a military disaster due to lack of military preparedness and adequate military forces. The feeling was cowardly, mean, and thoroughly un-British. … (p. 90)

This book was written with the intention of setting the record straight and expresses the indignation felt by many British ‘Malayans’ for the way in which they were blamed for the fall of Singapore. It would be fair to say that the image of colonial men and women dining and dancing away at Raffles Hotel, oblivious to the war around them, is still perpetuated, but is this an truthful representation or somewhat superficial?

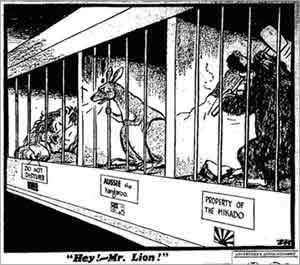

For Australia, the successful defence of Singapore was paramount to the safety of the country. As Beaumont (1996) comments the country’s defences ‘were fearfully thin’ (p. 26); with the four AIF divisions overseas - three in the Middle and the fourth division was scattered across Ambon, Timor, New Britain, and Malaya (two brigades) - this left the Militia to defend Australia (Beaumont, 1996). However, Britain’s priorities lay with the war in Europe and particularly the Middle East, an area into which reinforcements, armaments and aeroplanes had been directed, leaving Far East defence vulnerable, not only in Malaya, but also Hong Kong and Burma. A cartoon by Zec (Fig. 8) illustrates Australia’s frustration in trying to get Britain to face up to its responsibility it had for the security of the Dominion. Threatened by an ape (Japan) trying to knock down the partition wall between the cages, the kangaroo is attempting to attract the attention of the dozing lion; unfortunately it has a “DO NOT DISTURB” sign up. The irate expression on the face of the Kangaroo conveys the exasperation felt by the Australian Government and people for Britain’s inaction far better than words could. This cartoon was seen by a British audience – would it have provoked a reaction from them, and if so, what kind? A report in the Daily Mirror, entitled ‘Australia praises us’ (January 15, 1942) may shed some light on this. In this extract, the Mirror is quoting from an Australian newspaper from the previous day:

-

In a leading article the [Sydney] Sun states “the courageous British newspapers are uniting in a strong effort to shock Whitehall and the British public into a better realisation of what the loss of Malaya means to the Empire.”

With this in mind, perhaps the purpose of Zec’s cartoon was to bring to the public’s attention what the loss of Malaya would mean, more specifically, to Australia - that it would be under direct threat from Japan.

Figure 8. Philip Zec, Daily Mirror (London) January 24, 1942

| Page 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| Contents > “Roar Britannia?” by Bridget Deane |